As South Africa transitioned from apartheid, a group of photojournalists came to prominence covering the accompanying violence. They would not escape the events they captured unscathed, and became known as The Bang Bang Club. Here, one of the two surviving members reflects on South Africa then and now – and finds some frightening similarities.

My journey into photojournalism began from a place of deep anger when, during the 1980s, the South African system of apartheid appeared to be invincible and permanent.

I had no idea then that a rapid dismantling of white supremacy lay ahead. It seemed so unlikely that such a monolithic institution would, by 1990, be offering freedom to jailed black nationalist leaders and unbanning liberation organisations and even the demonised Communist Party.

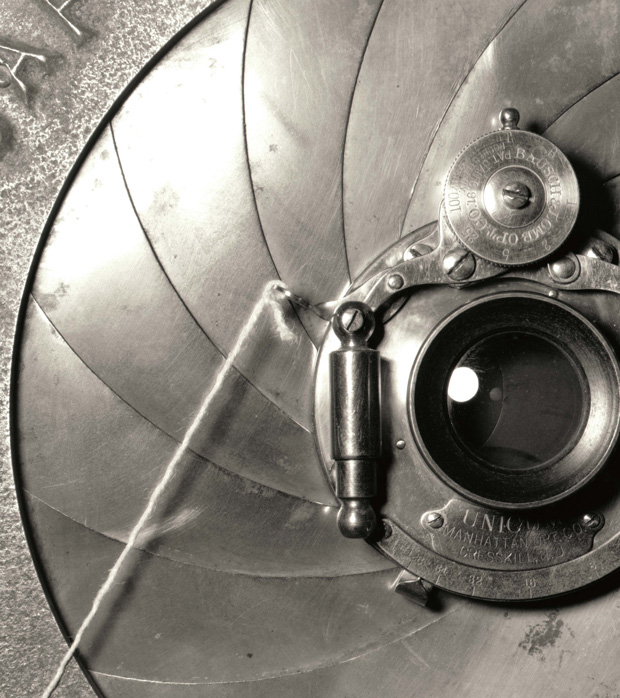

After Nelson Mandela’s release from prison, I was documenting the outlandish world of the bantustans, South Africa’s ethnic ‘homelands’, with an arcane large format camera, and spending much of my time following the strange interplay of national and local politics in the bantustan of Venda, in the north of the country. It was a long way from news photography.

But within months of Mandela’s release, a Pandora’s Box of state, political and ethnic violence erupted, mostly in the string of towns and cities that followed the veins of gold around Johannesburg. Nervously, I drove to a migrant workers’ compound in Soweto to document the violence of what became known as the Hostel War.

Murder, up close

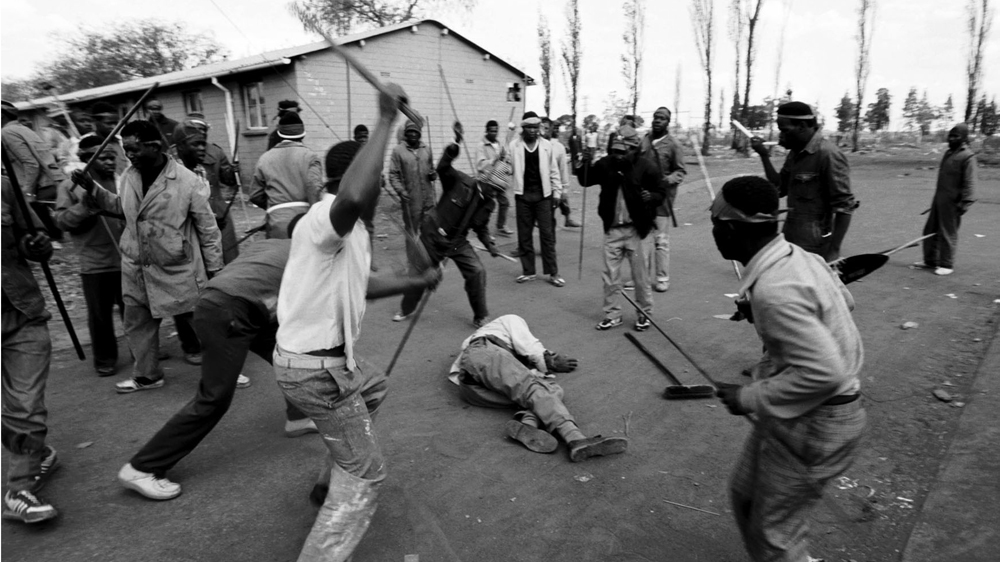

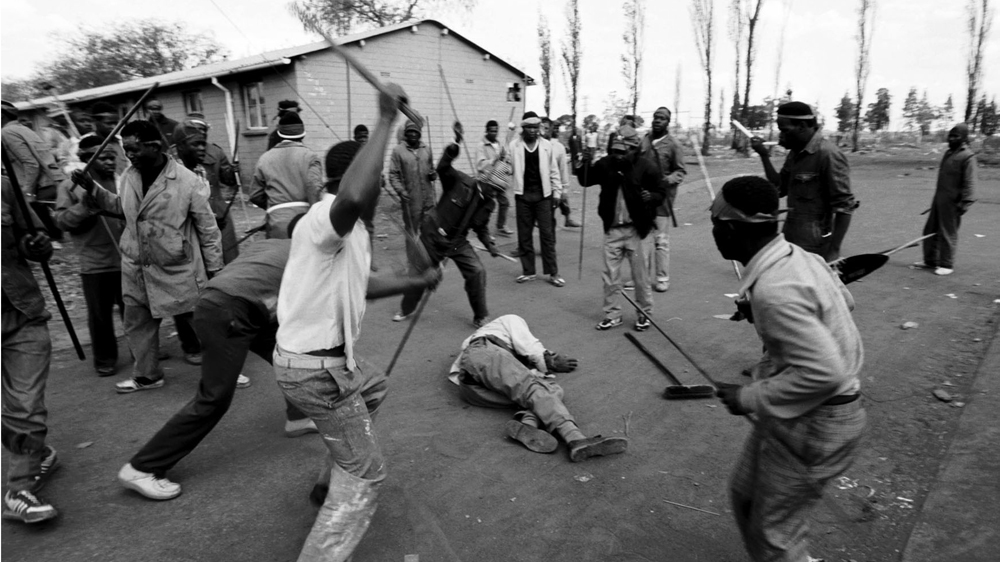

|

| In August 1990, I captured the killing of a suspected ANC supporter by Zulu supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party in Nancefield hostel in Soweto following a street conflict with ANC supporters [Greg Marinovich] |

I had ventured into a Zulu dominated hostel, alone, at the tail end of a battle between township residents and Zulu migrants. I was about to witness – and photograph – the horrifically intimate murder of a man the Zulu residents had identified as an ANC supporter, and hence an enemy. I was permitted to capture him being hacked and stabbed to death and then, somehow, to go on my way unhindered.

Those were the most disturbing moments of my life, to that point.

Friends suggested I take the images I had captured to the local offices of The Associated Press (AP), who purchased some and asked me to take more the next day.

Consumed by a desire to cover this almost invisible conflict, I began to shoot images regularly for AP and the legendary Sygma photo agency.

Although coming towards the end of their illustrious careers, some of the older hands of South African photojournalism, particularly Alf Kumalo and Peter Magubane, were still working full time at that point, and generously shared tips and insights with some of us newcomers. But, they felt uncomfortable covering the hard edge of a conflict where ethnic background often proved more damning than political positions – sometimes endangering black photographers, while whites had the advantage of being neither Zulu nor Xhosa and thus widely assumed to be without political links.

The 1990s were a strange time in South Africa. Even though the underlying conflict was all about race, it played out – on the surface at least – in black people killing other black people. Most of the violence on the ground took place between the ANC and the Inkatha Freedom Party, a Zulu-dominated political group covertly armed and aided by the state.

The beginnings of Bang Bang

|

| In this photograph taken in 1994, ANC supporting activists stand above a cap, still smoking from a point-blank range gunshot that killed one of their Self Defence Unit comrades while he was watching the FIFA World Cup. The shot was fired by a member of the Inkatha Freedom Party [Greg Marinovich] |

I soon encountered fellow beginner João Silva and we started to meet up before dawn to cover the Hostel War together. With few others capturing the violence, we grew to rely on each other’s judgment and support.

The way a mother looks at you when you photograph her dead son is not a moment to be forgotten or taken lightly. Grief is difficult and disturbing to cover, but it can also be dangerous. Sadness can swiftly turn to anger, endangering those who witness it.

The element of risk appeared magnified on those occasions when I worked alone, and there were times when I avoided death at the hands of a mob merely as a result of the peculiar dynamics of a crowd.

Despite this, there was a prevailing sense that journalists would be allowed to go about their business, although self-preservation dictated that Inkatha hostels became no-go zones and many sniper-lined roads off limits.

Kevin Carter was an old hand compared to us, but we knew each other. I barely knew Ken Oosterbroek, but he and Kevin were close friends, and when Ken hired João to work at the Johannesburg daily newspaper where he was chief photographer, we slowly all became friends.

When a local magazine editor, Chris Marais, began writing about a group of photographers making a name for themselves covering the political violence, we were collectively dubbed The Bang Bang Club – although his first article about us was titled ‘The Bang Bang Paparazzi’ and featured a right-wing photographer the rest of us avoided like the plague.

One of the results of this coverage was the creation of the false perception that we were the only ones covering the violence. In reality, there were radio reporters, writers and television journalists doing it day in, day out, but perhaps the idea of photographers and the images they offered made for a sexier story than maverick soundmen.

What the camera cannot capture

|

| In this photograph taken in 1992, an Inkatha Freedom Party supporter brandishes a handgun and fools around in Dobsonville hostel, Soweto, during a police raid to search for illegal weapons [Greg Marinovich] |

The hidden hand of state manipulation and violence was rarely glimpsed, and hardly ever photographed, but it was there.

Years later, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission would uncover evidence of policemen in mufti and blackface killing train commuters as part of a campaign to destabilise black communities.

I once witnessed a white man in civilian clothing jump out of an ambulance armed with an array of weapons and open fire on a crowd. On another occasion, I arrived at a shantytown where the ANC supporting residents told me that they had killed a white policeman with black shoe polish on his hands and face. For hours they had managed to stop the police retrieving the body, but the cops eventually succeeded. While I could not be sure if the story they told was true, years later a policeman spoke to me of the same incident.

Photography cannot capture these types of hidden truths.

Scarred and haunted

The fear I felt during those first few days, weeks and months did not diminish in the years that followed as I covered, among other things, South Africa’s bloody transition to democracy.

For some years, I travelled the world for the most prestigious news organisations and publications, buoyed by the exposure, yet haunted by the stories I covered. I was never able to develop a thick enough skin to shield myself from the lives and deaths I witnessed. Seeing a man killed is not something you can come to terms with, and nor should you. If I felt no pain, I would fear for my humanity.

By 1994, as the country lay on the cusp of its first democratic elections, my friends were beginning to die.

The photographer Abdul Shariff was killed early in the year in crossfire in Kathlehong.

Despite our reputation as The Bang Bang Club, João, Kevin, Ken and I had never travelled or worked together on the same story. That changed on one day in April 1994 – 10 days before the elections were due to be held.

It was a hot, violent day in Thokoza, and there was a sense that the ANC-Inkatha war was about to erupt into a major battle. That afternoon, Ken Oosterbroek was shot and killed. I was gravely wounded, after being shot with a high velocity assault rifle round to the chest, hand and buttocks. Within months, Kevin would commit suicide.

As South Africa gradually settled into an uneasy peace, I began to sense that my images had left too much unsaid; that they were too ambiguous or simply did not convey enough context. After all, decades of apartheid and white racism cannot be captured in a single frame showing two black political parties in conflict.

I wanted to restore what was lost to me and the people I had photographed through a thorough and complex retelling of my – and their – stories.

News is important, as are the wire services that we worked for, but they often lack the sort of depth and context that can only be gained on reflection. It takes time to understand complex situations; time that is not afforded to news photographers.

Along with João, I wrote The Bang Bang Club (Random House, 2000), which expounded on many of those photographs where the visual message was often not what was intended. It was also an exposition on conflict photography, from both a professional and personal perspective.

As South African society grew more normal, and I survived a few more injuries, I eventually drifted away from covering news and returned to my roots as a documentary filmmaker.

Joao kept at the hard news, spending the first decade of the 21st century rotating through Afghanistan and Iraq. It was in Afghanistan that he stepped on a landmine, losing both his legs and suffering horrific internal injuries. For more than three years he went from operation to operation, often on the brink of death. But he survived, and has slowly returned to shooting.

Out of sight, out of mind

|

| In this photograph taken in 1995 in Durban, an Inkatha Freedom Party supporting chief fires a handgun into houses during a rally in Umlazi Township. When he noticed me taking pictures, he turned on me and I had to beg him not to shoot [Greg Marinovich] |

During the 1990s, the township of Thokoza was one of the most violence-wracked parts of the country, and thus the site of much of my work. In the years since, I have repeatedly returned to follow the lives of the township’s former child soldiers, uncovering layers of information that can only be revealed with the passage of time.

I befriended some of the former fighters and spent years documenting their struggles with extreme poverty and the legacy of their experiences and losses.

As South Africa slowly degenerated from inspirational exemplar of courage and hope into a narrowing kleptocracy, my work with marginalised and disenfranchised communities increasingly reminded me of our dark past.

South Africa was almost imperceptibly beginning to regress and the resemblance with the 1990s was worrying.

In August of 2012, I went to the platinum-mining belt west of Johannesburg to learn more about a labour dispute that seemed to have extraordinary visual resonance with the events of two decades earlier. I was alarmed to discover that paramilitary police units had been deployed, and to witness the intransigence of the mine in its response to workers’ demands for decent wages and working conditions.

I spent the next day writing about the dispute and thus was not at Marikana on August 16, when the police opened fire, killing dozens of miners.

Marikana was the bloodiest incident in post-apartheid South Africa, yet even the horror captured by television cameras proved to be just a fraction of the truth.

As police claims of self-defence dominated local and international news, it became clear to me, prompted by Professor Peter Alexander’s speedy research, that the majority of the deaths had happened out of sight, and thus out of mind.

That the dominant narrative in the media ignored this is a sad reflection of media superficiality and deference to power.

Thus began my journey to discover what really happened on that day. My investigation in The Daily Maverick revealed a cover-up of police murder – out of site of the cameras – unprecedented in our democratic history. Richard Pithouse of Rhodes University called it “the most important journalism in post-apartheid South Africa”.

Over the course of a year, I continued to delve into the living and working conditions of the miners, as well as the ongoing arrest and torture of strike leaders and the persecution of survivors.

Marikana has become a watchword for a society on the brink of a popular uprising, for a revolution betrayed by greed. Once again, South Africa appears to be facing a crisis of identity and humanity.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.

This article first appeared in the March 2014 issue of the Al Jazeera Magazine. Download the magazine for iPads and iPhones here and for Android devices here.

Source: Aljazeera