By Maria Popova

“Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.”

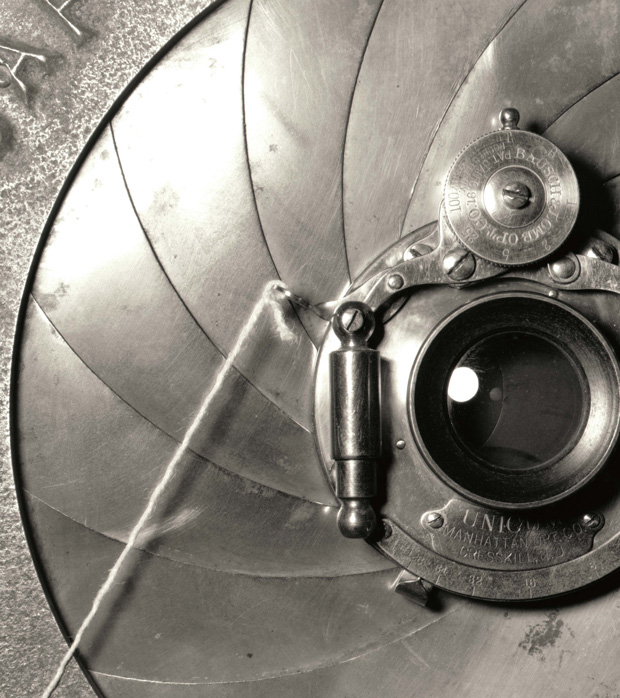

Ever since its invention in 1839, the photographic image and its steady evolution have shaped our experience of reality — fromchronicling our changing world and recording its diversity to helping us understand the science of emotion to anchored us to consumer culture. But despite the meteoric rise of photography from a niche curiosity to a mass medium over the past century and a half, there’s something ineffably yet indisputably different about visual culture in the digital age — something at once singular and deeply rooted at the essence of the photographic image itself.

Ever since its invention in 1839, the photographic image and its steady evolution have shaped our experience of reality — fromchronicling our changing world and recording its diversity to helping us understand the science of emotion to anchored us to consumer culture. But despite the meteoric rise of photography from a niche curiosity to a mass medium over the past century and a half, there’s something ineffably yet indisputably different about visual culture in the digital age — something at once singular and deeply rooted at the essence of the photographic image itself.

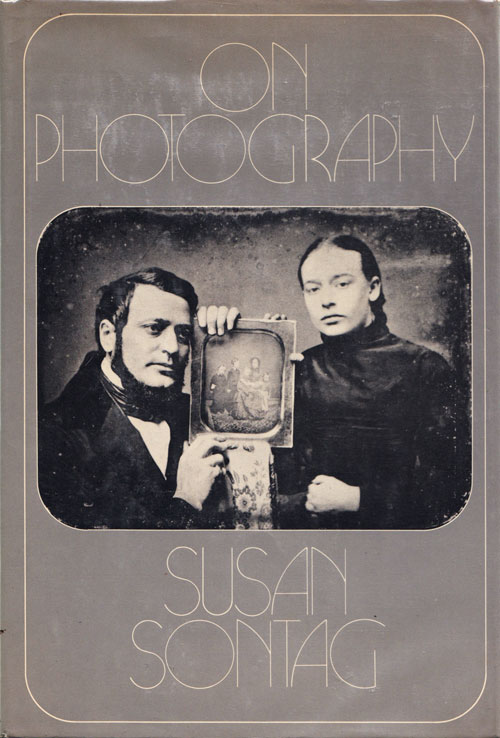

Though On Photography (public library) — the seminal collection of essays byreconstructionist Susan Sontag — was originally published in 1977, Sontag’s astute insight resonates with extraordinary timeliness today, shedding light on the psychology and social dynamics of visual culture online.

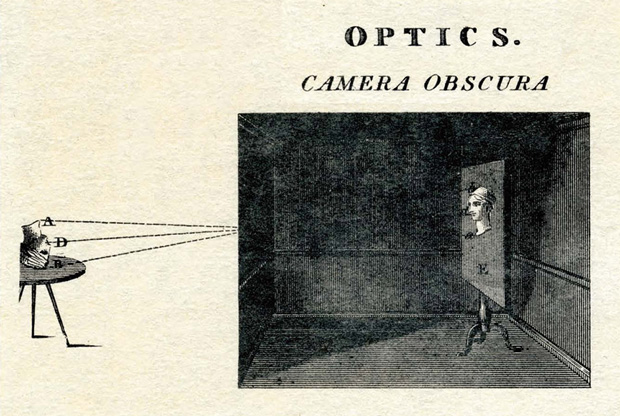

In the opening essay, “In Plato’s Cave,” Sontag contextualizes the question of how and why photographs came to grip us so powerfully:

Humankind lingers unregenerately in Plato’s cave, still reveling, its age-old habit, in mere images of the truth. But being educated by photographs is not like being educated by older, more artisanal images. For one thing, there are a great many more images around, claiming our attention. The inventory started in 1839 and since then just about everything has been photographed, or so it seems. This very insatiability of the photographing eye changes the terms of confinement in the cave, our world. In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe. They are a grammar and, even more importantly, an ethics of seeing. Finally, the most grandiose result of the photographic enterprise is to give us the sense that we can hold the whole world in our heads — as an anthology of images.

Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood. To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge — and, therefore, like power.

What makes this insight particularly prescient is that Sontag arrived at it more than three decades before the age of the social media photostream — the ultimate attempt to control, frame, and package our lives — our idealized lives — for presentation to others, and even to ourselves. The aggression Sontag sees in this purposeful manipulation of reality through the idealized photographic image applies even more poignantly to the aggressive self-framing we practice as we portray ourselves pictorially on Facebook, Instagram, and the like:

Images which idealize (like most fashion and animal photography) are no less aggressive than work which makes a virtue of plainness (like class pictures, still lifes of the bleaker sort, and mug shots). There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera.

Online, thirty-some years after Sontag’s observation, this aggression precipitates a kind of social media violence of self-assertion — a forcible framing of our identity for presentation, for idealization, for currency in an economy of envy.

Even in the 1970s, Sontag was able to see where visual culture was headed, noting that photography had already become “almost as widely practiced an amusement as sex and dancing” and had taken on the qualities of a mass art form, meaning most who practice it don’t practice it as an art. Rather, Sontag presages, the photograph became a utility in our cultural power-dynamics:

It is mainly a social rite, a defense against anxiety, and a tool of power.

She goes even further in asserting photography’s inherent violence:

Like a car, a camera is sold as a predatory weapon — one that’s as automated as possible, ready to spring. Popular taste expects an easy, an invisible technology. Manufacturers reassure their customers that taking pictures demands no skill or expert knowledge, that the machine is all-knowing, and responds to the slightest pressure of the will. It’s as simple as turning the ignition key or pulling the trigger. Like guns and cars, cameras are fantasy-machines whose use is addictive.

But in addition to dividing us along a power hierarchy, photographs also connect us into communities and nuclear units. Sontag writes:

Through photographs, each family constructs a portrait-chronicle of itself — a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness.

One has to wonder, however, whether — and how much — the family circle has been replaced by the social circle as we construct our online communities around photostreams and shared timelines. Similarly, Sontag notes the heightened use of photography in tourism. There, images validate experience, which raises the question of whether we engage in a kind of “social media tourism” today as we vicariously devour other people’s lives. Sontag writes:

Photographs … help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism. For the first time in history, large numbers of people regularly travel out of their habitual environments for short periods of time. It seems positively unnatural to travel for pleasure without taking a camera along. Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.

A way of certifying experience, taking photographs is also a way of refusing it — by limiting experience to a search for the photogenic, by converting experience into an image, a souvenir.

Out of those souvenirs we build a fantasy — one we project about our own lives, and one we deduce about those of others:

Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.

But Sontag’s most piercing — and perhaps most heartbreaking — insight about leisure and photography touches on our cultural cult of productivity, which we worship at the expense of our ability to be truly present. For most of us, especially those who find tremendous fulfillment and absorption in our work, Sontag’s observation about the photograph as a self-soothing tool against the anxiety of “inefficiency” rings terrifyingly true:

The very activity of taking pictures is soothing, and assuages general feelings of disorientation that are likely to be exacerbated by travel. Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture. This gives shape to experience: stop, take a photograph, and move on. The method especially appeals to people handicapped by a ruthless work ethic — Germans, Japanese, and Americans. Using a camera appeases the anxiety which the work-driven feel about not working when they are on vacation and supposed to be having fun. They have something to do that is like a friendly imitation of work: they can take pictures.

At the same time, photography is both an attempted antidote to our mortality paradox and a deepening awareness of it:

All photographs are memento mori. To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.

This seems especially true, if subtly tragic, as we fill our social media timelines with images, as if to prove that our biological timelines — our very lives — are filled with notable moments, which also remind us that they are all inevitably fleeting towards the end point of that timeline: mortality itself. And so the photographic image becomes an affirmation of our very existence, one whose power is invariably addictive:

Needing to have reality confirmed and experience enhanced by photographs is an aesthetic consumerism to which everyone is now addicted.

It would not be wrong to speak of people having a compulsion to photograph: to turn experience itself into a way of seeing. Ultimately, having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it, and participating in a public event comes more and more to be equivalent to looking at it in photographed form. That most logical of nineteenth-century aesthetes, Mallarmé, said that everything in the world exists in order to end in a book. Today everything exists to end in a photograph.

On Photography remains a cultural classic of the most timeless kind, with every reading unfolding timelier and timelier insights as our visual vernacular continues to evolve. Complement it with 100 Ideas That Changed Photography, the curious legacy of image manipulation before Photoshop, and the history of photography, animated.

For more of Sontag’s brilliant brain, see her wisdom on writing, boredom, sex,censorship, and aphorisms, her radical vision for remixing education, her insight on why lists appeal to us, and her illustrated meditations on art and on love.

Source: http://www.brainpickings.org/index.php/2013/09/16/susan-sontag-on-photography-social-media/